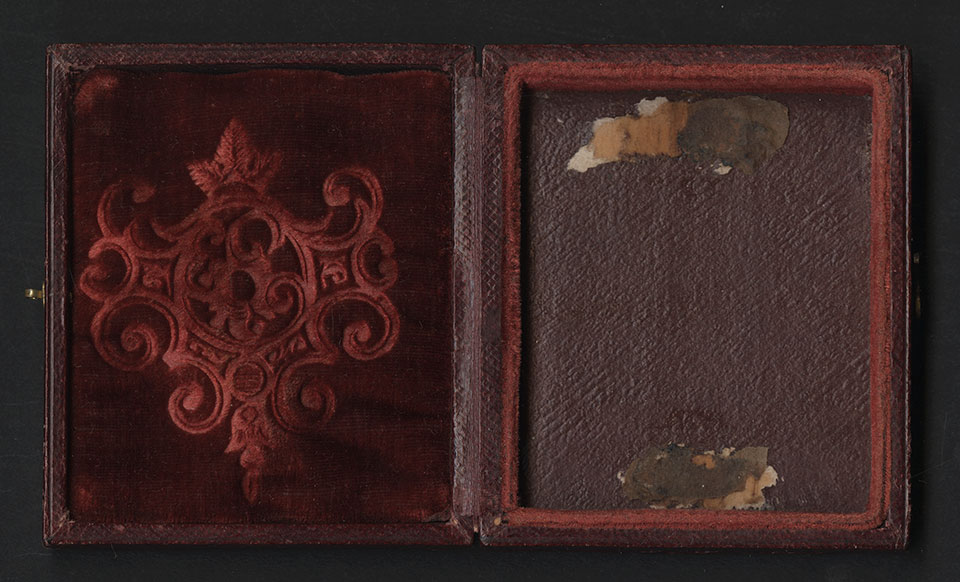

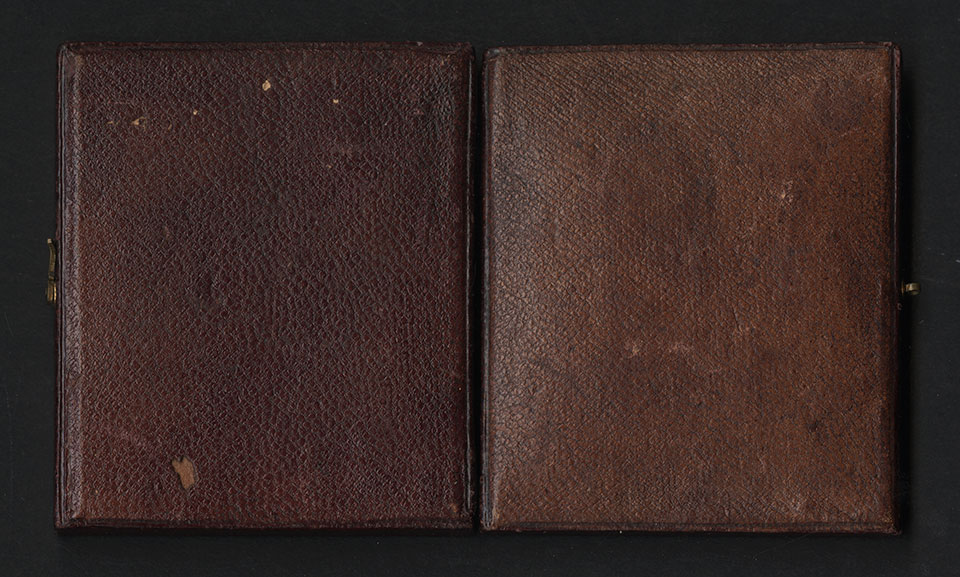

“This 9th plate daguerreotype of a gentleman with a sword belt and sword is in a well-bound original-to-the-plate-package English style case.

Evidently, the plate-package was originally glued into the case to prevent it from falling out. The package was removed, breaking the bond. In order to retain the package, an American metal preserver was put around the package.”

– Grant Romer

| Kaplan Collection | Known Images |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

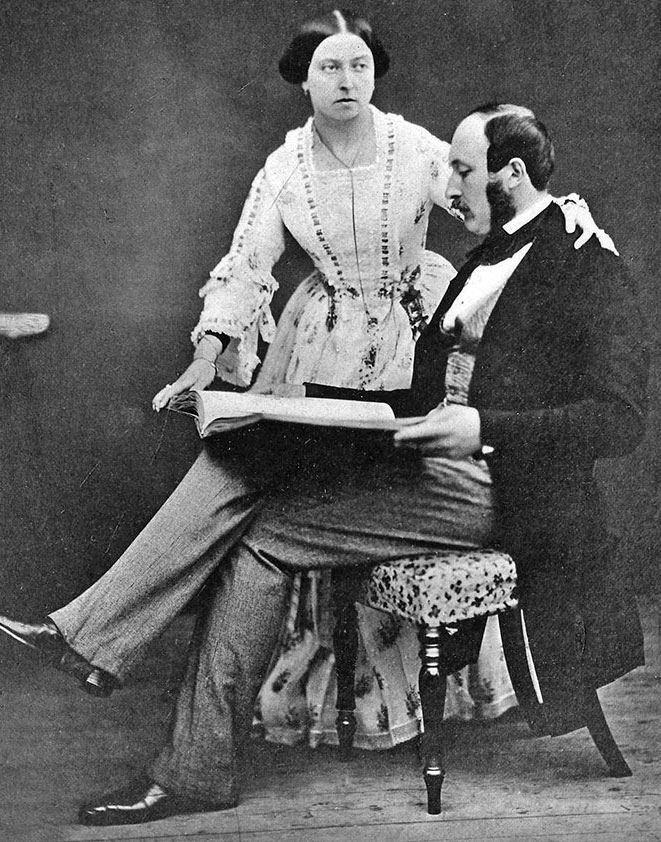

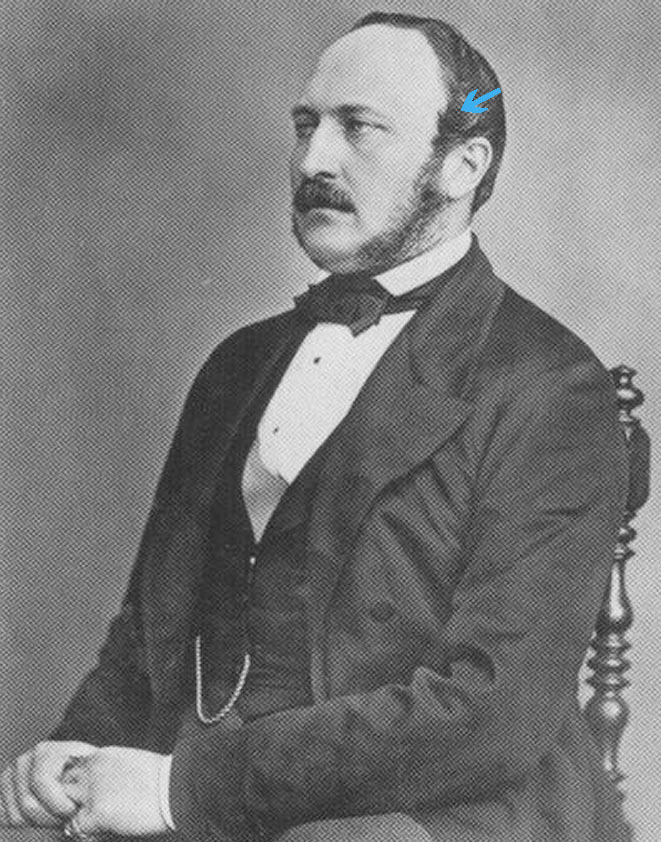

The Prince Albert comparisons are the most challenging I have encountered. Certainly, there are a number of compelling similarities. And yet, I was not convinced this man was Prince Albert. The chin bothered me. It seemed more shallow than in his known photographic images. However, we can see that in his known photographic images he is growing a double chin which increases in size as he ages and gains weight.

The mustache in his known photographic images is full and of quite a different construction to the minor handlebar mustache of the daguerreotype. In his know photographic images Albert’s chinstrap beard is trim, not the fashion seen in the daguerreotype, a chinstrap beard with modified muttonchops.

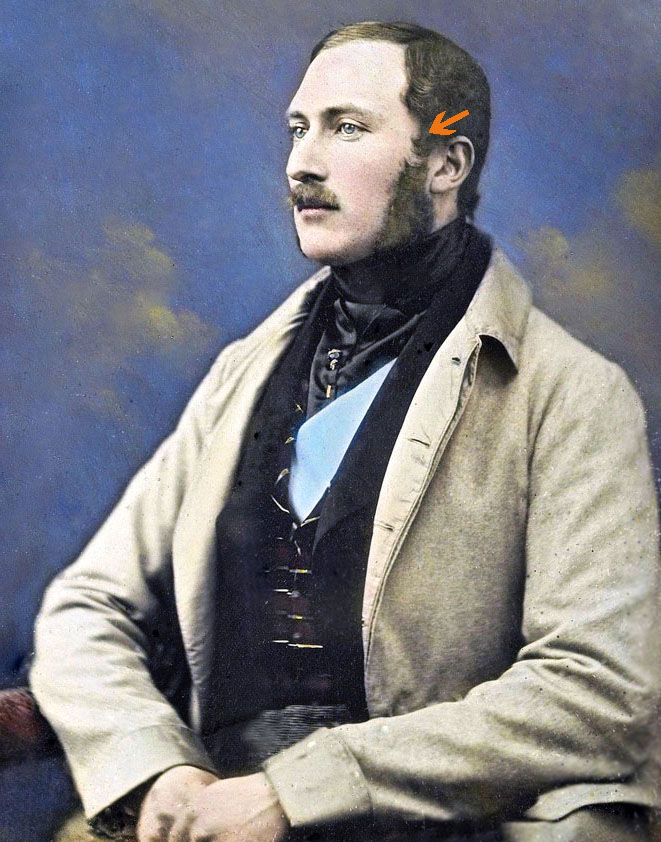

In the daguerreotype, to the extent we can see his ear, all elements are either similar or identical to his known ear: the free-hanging lobule; tragus; helix and antihelix; and the cavum conchae. From what we can see, there is no reason to think it is not the same ear.

Please see the slightly upturned hairs at the points of the purple, orange, yellow, and blue arrows. This was the catalyst that convinced me that this gentleman is Prince Albert.

Post Script

October 10, 2016

The occasion of the photograph, certainly one of the earliest British-made daguerreotypes, is unknown. If Albert left a daily memoir, perhaps the very date of the photograph can be learned, as well as the occasion.

Shortly after October 10, 1839, Queen Victoria described Albert’s facial hair. We read, from her journal, “Albert is really quite charming, and so excessively handsome, such beautiful blue eyes, an exquisite nose, and such pretty mouth with delicate mustachios and slight but very slight whiskers”

It has to be early, and I am thinking perhaps it is extremely early. Is the face we see in the daguerreotype not the very same as Victoria’s description?

I think that this daguerreotype could have been made as early as the Fall of 1841.

Post Script

March 8, 2021

This is a very early daguerreotype, likely made at the time of a public ceremony honoring Prince Albert.

This is definitely one of the very first daguerreotypes made in England.

It seems likely that this daguerreotype could have been taken soon after Albert walked off the boat! The more I think about it, the more I think so.

It seems likely to me that Victoria never saw this daguerreotype, nor, I surmise, did Albert.

Future historians will surely wonder where and how I acquired the Prince Albert daguerreotype. As always, in my search for any information surrounding each piece, I tried to investigate its source to the fullest extent possible. In this instance, I spoke with the seller on the telephone, a Jersey City/Hoboken area telephone number. The individual seemed to be uneducated, and foreign born. I remember thinking that the person I was speaking with might be a servant in the home of the deceased owner of the daguerreotype. I merely imagined it so. The person at the other end of the line was very reluctant to speak with me, seeming apprehensive or fearful. That is the way I recall it.

Post Script

April 26, 2021

This is a very early daguerreotype, perhaps made at the time of a public ceremony honoring Prince Albert. The occasion might be one of his arrivals on British shores. Historians will know the possible dates.

Clearly, this is one of very first daguerreotypes made in England.

It seems likely early that this daguerreotype could have been taken soon after Albert walked off the boat! The more I think about it the more I think it so. This daguerreotype could be … early.

It seems likely to me that Victoria never saw this daguerreotype, nor, I surmise, did Albert. It was made, I think, not for Albert, but for the “occasion”, and this daguerreotype was likely an honored possession of a chartered civil group of some sort.

Future historians will surely wonder where and how I acquired the Prince Albert daguerreotype. As always, in my search for any information surrounding each piece of the collection, I tried to go back in its history as far as possible. In this instance I had a little success, having spoken with the seller on the telephone, a Jersey City area code. I do not remember whether male or female. The individual seemed to be uneducated, middle aged and foreign born. I remember thinking that the person I was speaking with might be a servant in the home of the deceased owner of the daguerreotype. I merely imagined it so. The person at the other end of the line was reluctant to speak with me, seeming apprehensive. I remember it so.

I was delighted to come across an early daguerreotype of Prince Albert in the Kaplan Collection, and I am impressed by Mr. Kaplan’s diligent work in demonstrating that this and the later photographs of Queen Victoria’s husband are one and the same. The evidence Mr. Kaplan brings out to support this is impressive in its detail. The hours of diligent sleuthing that led to the identification of Prince Albert bring to mind that other, albeit fictional, 19th century British celebrity, Sherlock Holmes. Future researchers of this remarkable German nobleman, whose life was devoted to his adopted country, now have a reliable image of the Prince Consort in his younger years.

– Jules Stewart

Jules Stewart is the author of Albert: a Life, published by I.B. Tauris Ltd. in 2011 and available on Amazon.

53 Blenheim Crescent

London W11 2EG

United Kingdom

E-mail: julesstewart@gmail.com

Website: http://www.julesstewart.com/