© Albert Kaplan 2020

| Kaplan Collection | Known Image |

|---|---|

|

|

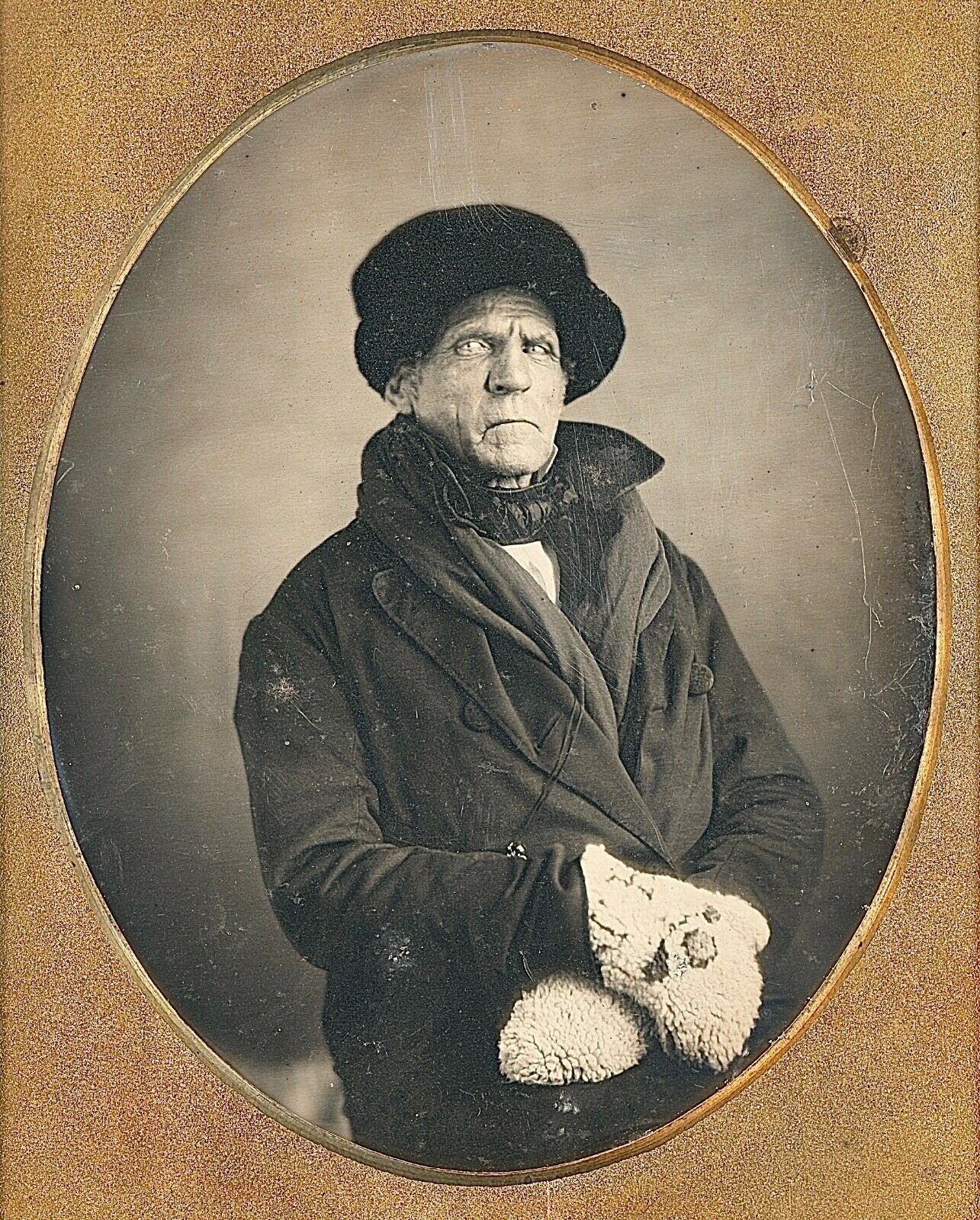

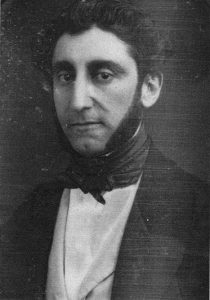

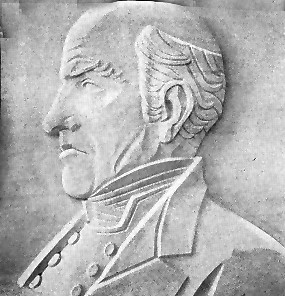

Without knowing that the sitter is the great Judah Touro, this quarter plate daguerreotype is a masterpiece of daguerreian portraiture.

During the past 25 years, and the millions of cased images I have examined, this daguerreotype stands alone at the Mt. Olympus of 19th Century photographic portraiture.

Holding this daguerreotype in my hand was a deeply moving experience. I was overwhelmed.

The above image was provided to me by the gentleman from whom I purchased this daguerreotype. Hopefully, in early 2021, I will be able to take this daguerreotype, as well as the entire collection, to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY. It is unlikely their technicians can improve upon it. The quality of this image is superb.

The initials, J T, can almost be made out on his mittens.

Certainly, the housing is original. The cover is missing.

This daguerreotype must have been kept in a vault.

The first of the following monographs was written

by Evan Sparks

Judah Touro was a leading merchant and philanthropist during the early days of our nation, known for benefactions throughout the country, but especially in Louisiana and Rhode Island. Born in 1775 in Newport, Rhode Island, Touro was the second son of Rabbi Issac Touro, leader of Newport synagogue.

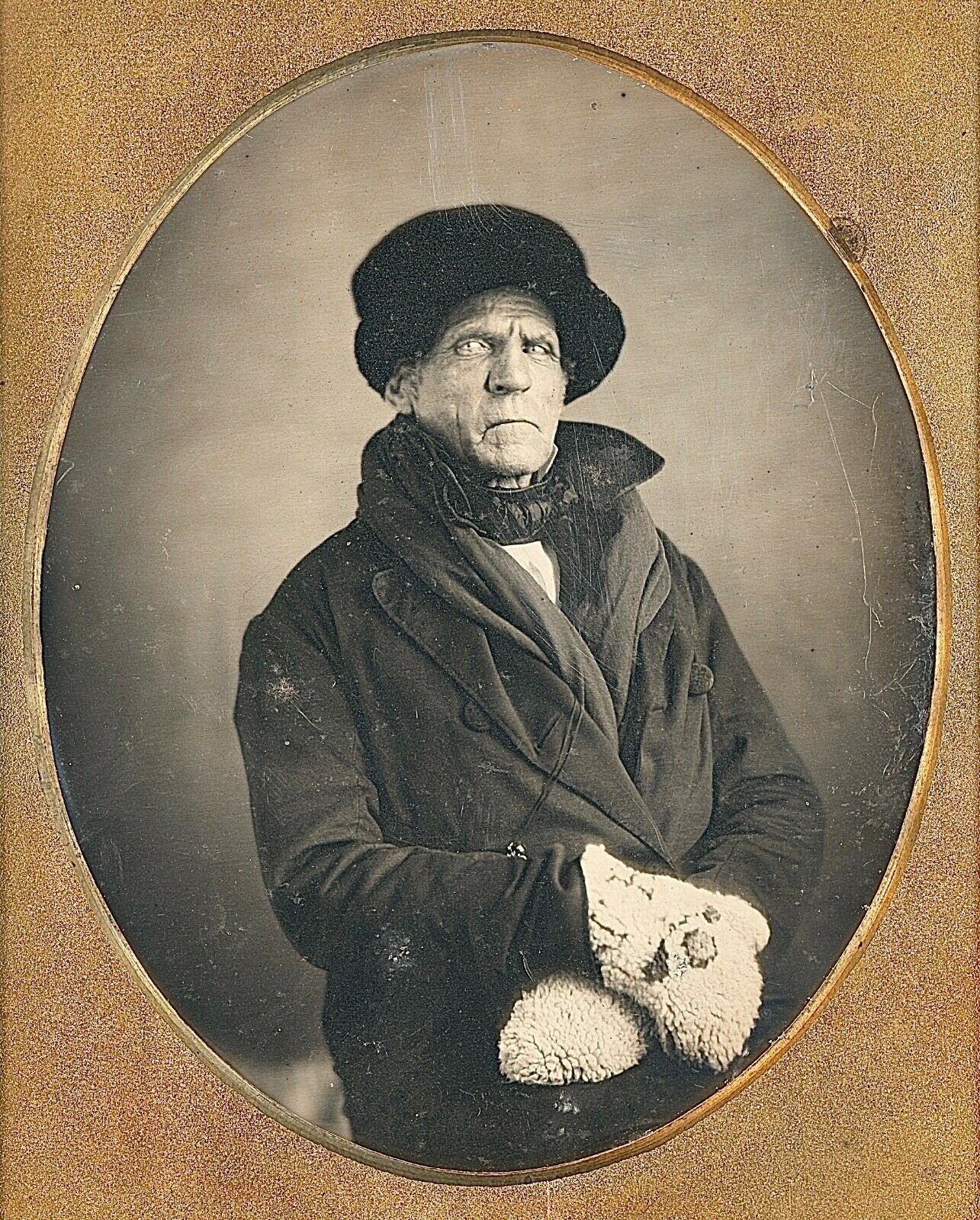

Constructed in 1763, and now known as the Touro Synagogue due to the gifts and service of the Touro family, the Newport assembly was the recipient of a famous 1970 letter on religious liberty from George Washington. “The government of the United States” wrote Washington, “which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens…May the children of the stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of other inhabitants.”

Touro remained a devout Jew, although for most of his life he was without a synagogue. When he arrived in New Orleans, his co-religionists in the city could be counted on two hands; as late as 1826, there were no more then a few hundred Jews in all of Louisiana. In 1828, Touro supported the founding of New Orleans’ first synagogue, which after some years divided into separate congregations in the Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions. Tour, by then quite wealthy, gave generously to both congregations and attended the Sephardic gathering. (In 1881, the synagogues merged, and today the combined congregation is named for its benefactor.) Touro also created and funded numerous Jewish relief agencies and Hebrew schools in New Orleans.

Touro gave liberally and ecumenically. In 1824, he erected a free public library. He purchased a Christian church building and assumed its debts, while allowing the congregation to use the building rent-free in perpetuity. When a friend suggested the property might be valuable if sold for commercial purposes, Touro responded, “I am a friend to religion and I will not pull down the church to increase my means!”

Touro died in 1854. In his will, he bequeathed $500,000 to institutions around the country – more than half of which went to non-Jewish causes. (As a percentage of GDP, these gifts would approximate $2 billion today.) The will includes Touro Synagogue and Tour infirmary; various benevolent societies and hospitals; orphanages, almshouses, and asylums; libraries and schools; and relief for Jews overseas. According to one contemporary observer, ” He gave ten times more then any Christian in the city to aid the cause of Christians in the land of Judaea.”

He also gave thousands of dollars each to 23 Jewish congregations in 14 states – especially the Newport synagogue, where he endowed the cemetery in which he was laid to rest, the final surviving member of the Tour family line. “The last of his name,” reads his tombstone, “he inscribed it in the Book of Philanthropy to be remembered forever.”

Jerry Klinger is president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

www.jashp.org

Judah Touro

By Jerry Klinger

“To the Memory of Judah Touro

Born Newport, R.I., June 16, 1775

Died New Orleans, La. Jan. 18, 1854

Interred here, June 6

“The last of his name He inscribed it in the Book of Philanthropy

To be remembered forever”

Amos and Judah – venerated names,

Patriarch and prophet press their equal claims,

Like generous coursers running “neck to neck”,

Each aids the work by giving it a check,

Christian and Jew, they carry out one plan,

For though of different faith, each is in heart a Man

– Oliver Wendell Holmes

He gathered money with honest Judaical eagerness,

but gave it away with true Christian liberality[1]

For Jews, Touro was a contradiction in purpose and motivation. Some modern Jewish historians such as Bertram Korn[2] saw him as a Scrooge needing to be shown the path to redemption before his passing. Other Jewish historians such as Leon Huhner[3] saw him as an American patriot, a faithful and generous Jew. Most historians paid little attention to him except for his famous and extraordinary will. His benefactions were forgotten once the money was gone. Even his generosity to the Jews in Jerusalem’s Old City, which began the foundation of modern Jerusalem, was obscured.

“Be it known that on this sixth day of January, in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and fifty-four, and of the independence of the United States of America the seventy eighth, a quarter before 10 o’clock am.

Before me, Thomas Layton, a Notary Public, in and for the city of New Orleans[4], aforesaid, duly commissioned and sworn, and in presence of Messrs. Jonathan Montgomery, Henry Shepherd Jr. and George Washington Lee, competent witnesses, residing in said city, and hereto expressly required-

Personally appeared Mr. Judah Touro, of this city, merchant whom I, the said Notary, and said witnesses, found sitting in a room at his residence, No. 128 Canal Street, sick of body, but sound in mind, memory, and judgment, as did appear to me, the said Notary, and to said witnesses. And the said Mr. Judah Touro requested me, the Notary, to receive his last will or testament, which he dictated to me, Notary, as follows, to wit, and in presence of said witnesses:

a. declare that I have no forced heirs.

b. desire that my mortal remains be buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Newport, Rhode Island as soon as practicable after my decease.

c. nominate and appoint my trust and esteemed friends Rezin Davis Shepherd of Virginia, Aaron Keppel Josephs of New Orleans, Gershom Kursheedt[5] of New Orleans, my testamentary executors, and the detains of my estate…..

………………

6. I give and bequeath to the Hebrew Congregation the “Dispersed of Judah” of the city of New Orleans all that certain property situated in Bourbon Street….

7. I give and bequeath to found the Hebrew Hospital of New Orleans the entire property purchased for me, at the succession sale of the late C. Paulding, upon which property the building now known as the “Touro Infirmary” is situated.

8. I give and bequeath to the Hebrew Benevolent Association of New Orleans…..

9. I give and bequeath to the Hebrew Congregation “Shangarai Chassed” [6]of New Orleans….

10. I give and bequeath to the Ladies Benevolent Society

11. I give and bequeath to the Hebrew Foreign Mission Society

12. I give and bequeath to the Orphan’s Home Asylum of New Orleans…

………………

14. I give and bequeath to the St. Armas Asylum for the relief of destitute females and children…

………………

16. I give and bequeath to the St. Mary’s Catholic Boy’s Asylum…

………………

18. I give and bequeath to…. the Firemen’s Charitable Association, Seamen’s Home, created an Alms house in New Orleans, to the city of Newport, R.I., for the creation of a public park, to the Redwood Library in Newport, Hebrew Congregation, Ohabay Shalome –Boston, Hebrew Congregation of Harford Conn, New Haven Conn., Jew’s Hospital Society of New York, Hebrew Benevolent Society New York, Talmud Torah School, Shearith Israel, B’nai Jeshurun of New York, Shangari Tefila, New York, Hebew Education Fund, Philadelphia, Congregation Ahabat Israel, Baltimore, Shearith Israel, Charleston, S.C., Mikve Israel, Savannah, Ga., Hebrew Congregation, Montgomery, Ala., Memphis, Tenn., Adas Israel, Louisville, Ky., Bnai Israel Cincinnati, Ohio, Talmud Yelodim, Cincinnati Ohio, Jews Hospital Cincinnati, Ohio, Tifereth Israel, Cleveland, B’nai El St. Louis, Mo., Beth El, Albany, Asylum of Orphan boys, Boston, female Orphan Asylum of Boston, Mass. Female Hospital…

………………

26. I give and bequeath to t he North American Relief Society for the Indigent Jews of Jerusalem, Palestine………

27. It being my earnest wish to co-operate with the said Sir Moses Montefiore of London, Great Britain, in endeavoring to ameliorate the condition of our unfortunate Jewish Brethren, in the Holy Land, and to secure to them the inestimable privilege of worshipping the Almighty according to our religion without molestation. I therefore bequeath the sum of fifty thousand dollars.

………………

55. I give and bequeath ten thousand dollars for the purpose of paying the salary of a Reader or Minister to officiate in the Jewish Synagogue of Newport, Rhode Island, and to endow the Ministry of the same, as well as to keep in repair and embellish the Jewish Cemetery in Newport aforesaid.

56. I give and bequeath the sum of five thousand dollars to Miss Catherine Hays now of Richmond, Virginia, as an expression of the kind remembrance in which that esteemed friend is held by me.

………………

61. I give and bequeath the sum of three thousand dollars to my respected friend the Rev. Isaac Leeser[7], of Philadelphia as a token of my regard.

62. I give and bequeath the sum of three thousand dollars to my friend the Rev. Theodore Clapp, of New Orleans in token of my remembrance.

………………

Judah Touro died January 16, 1854. He passed away quietly as he had lived. He was mourned by many especially after the American and international publication of his will. In life few really knew or understood him. Many Jewish communities were astonished by the bequeaths from the obscure recluse from the New Orleans.

The people of New Orleans knew him. They knew his generosity, his asceticism and his eccentricities. They knew of his deep respect for the meaning and worth of faith, Jewish or not. They never knew to what extent Judah Touro was and had lived his life as a Jew. It did not matter in New Orleans where Protestant, Catholic, Jewish and Voodoo mixed. What mattered was the quality of the man. What mattered most were the American frontier values. Judah Touro’s life was one of honesty, hard work, dedication to community, faith, patriotism and philanthropy. He repeatedly demonstrated his willingness to risk all for something he believed in. He was the ideal citizen, the ideal American. When he died he was mourned deeply, sincerely and fully by Jew and Christian alike.

“In 1658, a group of fifteen Jewish families, hearing about Roger William’s “Lively Experiment,” where the civil government was devoid of power over spiritual matters, sailed into Newport harbor. These Sephardim (the Hebrew word for Jews from the region in the Iberian Peninsula that is now Spain and Portugal), who like their ancestors were seeking a haven from religious persecution, founded the second Jewish settlement in the colonies and Congregation Jeshuat Israel (Salvation of Israel). In 1677, they purchased and consecrated property as a Jewish cemetery, a place where they could bury their dead according to Jewish tradition.

With the assurance of religious freedom and liberty of conscience, as promised by Governor Roger Williams, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations offered more than a refuge; it offered unparalleled social and economic opportunities.”[8]

The Jewish community of Newport flourished but grew slowly. It was not until 1758 that the community was large enough that they felt they could support a permanent spiritual leader, a Rabbi. They sent a request to the center of Rabbinic Sephardic life, Amsterdam. Twenty year old Isaac Touro, a trained but not yet ordained Rabbi, was sent to the growing Newport community as their spiritual leader. It was quite probable that Touro, whose family name was originally de Touro in Spain when they were still under suspicion for being Maranos,[9] secret Jews, was sent not as top choice. America was far from the center of Jewish learning and community. European Jewry was not flooding to America. Despite his youth, Touro turned out to be an excellent choice.

Within a year of his arrival he convinced the Newport Jewish community to purchase a tract of land for the future construction of a permanent house of worship, (1759).

In early Colonial America, Jewish religious services were commonly held in private homes for two reasons. The first reason was that Jewish religious services were generally tolerated if they were not seen or did not create a nuisance. By the early 18th century the British were finally prevailed upon to permit the construction of the first permanent Jewish house of worship in the Colonies, New York’s Shearith Israel in 1730.[10] Afterwards, the construction of permanent Jewish houses of worship was no longer an issue in the other Colonies. The second reason was that Jewish communities were small and the construction and maintenance of a house of worship was beyond many of their financial capabilities.

Newport was a rapidly expanding port and mercantile center. Touro raised the monies for the land and later for a synagogue from the Newport community and from solicitations of help to Jewry around the world and in the other Colonies. Touro provided colonial architect Peter Harrison[11] with design ideas from what he remembered of the great Sephardic synagogues in Holland. One curious design requirement must have seemed incongruent almost baffling in its request to Harrison. Touro wanted a secret escape doorway behind the bemah (the readers table ) built to a tunnel that led to the rear of the synagogue. Touro and the Jewish community of Newport were not afraid of Indian attacks. They were afraid of their history as Jews, even in Colonial America. The secret doorway to the escape tunnel still exists in the modern functioning synagogue today– now part of the United States Park Service.[12]

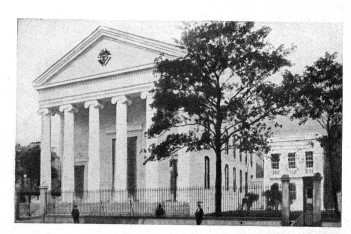

Yeshuat Israel (Touro Synagogue –Newport, Rhode Island)

Four years later, December 2, 1763, Chanukah, Yeshuat Israel Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, before 80 members of the Jewish community and numerous Christian friends, dedicated their beautiful new synagogue building. Among the attendees was the Reverend Ezra Stiles who later would be president of Yale University.[13]

Interior of Synagogue

The Newport Mercury described the dedication:

“In the afternoon was the dedication of the new Synagogue in this Town. It began by a handsome procession in which was carried the Books of the law to be deposited in the Ark. Several Portions of Scripture, and of their Service with a Prayer for the Royal Family were red and finely sung by the Priest and People. There were present many Gentlemen and Ladies. The Order and Decorum, the Harmony and Solemnity of the Musick, Together with a handsome Assembly of People in an Edifice, the most perfect of the Temple kind perhaps in America, and splendidly illuminated, could not but raise in the mind a faint idea of the Majesty and Grandeur of the Ancient Jewish Worship mentioned in Scripture.”[14]

“In June, 1773, the Rev. Isaac Touro married Miss Reyna (Richea) Hays, the daughter of Judah Hays, a prominent merchant of New York, and Newport. The ceremony was performed by the Rev. Isaac Karigal, a rabbi from Jerusalem who was visiting America at the time. The bride’s brother was Moses Michael Hays, who was born in New York City in 1739, though several writers state that he had been born in Lisbon, Portugal. Hays later became one of the leading merchants in Boston, and subsequently figured among the patriots of the Revolutionary War.”[15]

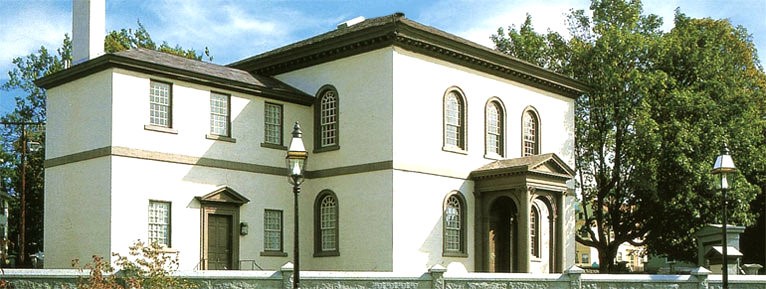

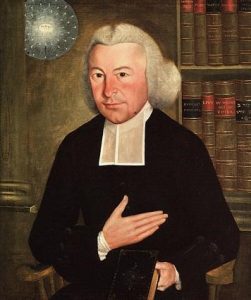

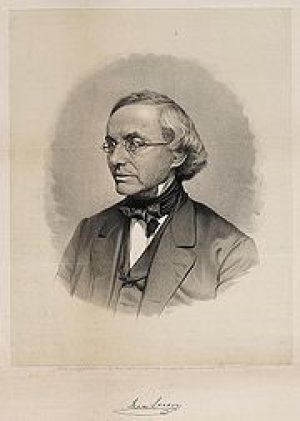

Rabbi Haim Isaac Carigal

Rev. Ezra Stiles

Rabbi Haim Isaac Carigal [16] traveled throughout the Jewish world seeking funding and support for the Jewish community in Palestine. He remained in Newport for six months befriending and deeply influencing Reverend Stiles in their more than 28 meetings about faith, Judaism, and the importance of the Hebrew language. While President of Yale in later years, Rev. Stiles tried to instill Hebrew as a living language amongst its students. Lectures, commencement addresses and even Valedictory speeches at graduation were delivered by him and his students in Hebrew. The effort to plant Hebrew as a national language failed.

In 1774, the Touro’s first child was born. They named him Abraham. A year later, while the Battle of Bunker Hill raged outside of Boston, their second child was born, June 16, 1775. They named him Judah. A third child was born to the Touros, a girl, Rebecca, in 1779. In 1824, Rebecca Touro (Lopez)[17],[18] petitioned the Rhode Island legislature to preserve the Newport synagogue using funds from the estate of her brother Abraham Touro. The building was preserved even though there were no Jews living in Newport.

The 1770’s in Colonial America were years of turmoil and a deepening impending rift between the relationship between Britain and her American Colonies. The rift, which might have been healed ruptured into rebellion and open war. The American Revolution began in 1776. The British quickly captured Newport. The vast majority of the Jews of Newport, choosing to link their fates to the American Revolutionary cause, abandoned their homes, their businesses and property, fled. The British destroyed much of Newport. Rev. Touro remained behind to protect the Torahs and the synagogue. The building was not destroyed. The British converted it into a hospital for their soldiers.

With no Jewish community left in Newport, Rev. Touro moved his family to New York seeking employment. He found none. (1781) He accepted a position to head the Jewish community in Jamaica. He moved to Kingston. Rev. Isaac Touro died there three years later.

Impoverished, his widow and the three children returned to live with her brother Moses Michael Hays of Boston.

Moses Michael Hays

“While some colonial Jews experienced difficulty living both as Jews and Americans, Boston’s Moses Michael Hays created a different experience. Boston’s most prominent 18th-century Jewish citizen, Hays set a high standard for civic leadership and charity. Without the companionship and support of an organized Jewish community and without legal guarantees of religious freedom, Hays thrived in the “first circles” of Boston society while publicly practicing his Judaism.

Moses Michael Hays was born in New York City in 1739 to Dutch immigrants Judah Hays and Rebecca Michaels Hays. Judah Hays took his son into his shipping and retail business and, upon his death in 1764, left him the business and largest share of his assets.

Judah Hays left Moses Michael Hays something else as well: a firm grounding in his Jewish faith and responsibilities. Moses served New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel as second parnas (vice-president) in 1766 and parnas in 1767. Even after moving to Boston, Moses retained an attachment to Shearith Israel, appearing on its donor list throughout his life.

In 1766, Moses married Rachel Myers, younger sister of famed New York silversmith Myer Myers. In 1769, the couple moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where Hays continued his shipping business. Business reverses landed Hays in debtor’s prison but, under a 1771 reform law, Hays liquidated his assets, gave them to his creditors and was set free. He immediately reestablished himself in the trans-Atlantic trade.

The American Revolution brought Hays a new challenge as a Jew. In 1775, seventy-six men in Newport were asked to sign a declaration of loyalty to the American colonies that included the phrase, “upon the true faith of a Christian.” Hays publicly objected to the phrase and refused to sign, instead offering a letter affirming his belief that the Revolution was a just cause. When, after much wrangling, the Christian portion of the oath was omitted, Hays affixed his name.

Hays and his family left Newport for Boston ahead of the British occupation in 1776. Hays opened a shipping office in Boston. He was among the first merchants there to underwrite shipbuilding, trade and insurance to newly opened Far Eastern markets. In 1784, Hays became a founder and the first depositor of the Massachusetts Bank, still doing business today as Fleet Bank Corporation. With his close friend Paul Revere and fourteen other Boston businessmen, Hays formed several insurance companies.

Hays helped establish the New England Masonic movement. When Hays was accepted into the Massachusetts Lodge in November 1782, he was the only Jew, the first signal that Hays had won acceptance in Boston’s elite society. In 1792, the lodge members elected Hays their Grand Master. Paul Revere served as his deputy.

The Hays family filled a large brick home with 15 rooms and 31 windows in Boston’s fashionable Middle (now Hanover) Street. The Hays had seven children…..

Samuel May, Louisa May Alcott’s grandfather, was a close childhood friend of the Hays and Touro children and recalled “Uncle and Aunt Hays” for their pride in their Judaism.

“If the children of my day were taught among other foolish things to dread, if not despise Jews, a very different lesson was impressed upon my young heart. … [The Hays] house … was the abode of hospitality. … He and his truly good wife were hospitable, not to the rich alone, but also to the poor. … I witnessed their religious exercise, their fastings and their prayers. … [As a result] I grew up without prejudice against Jews—or any other religionists.”

As Boston lacked a synagogue, Moses Michael Hayes conducted regular worship services at home. The household library contained dozens of Hebrew books. The Jewish commandment to dispense charity directed much of what the Hays family did for Boston and its citizens. Moses Michael Hays provided financial support to beautify Boston Common, establish theaters and endow Harvard College. His children and nephews went on to distinguished and charitable lives. Son Judah Hays was the first professing Jew elected to Boston public office. Hays descendants helped found the Boston Athenaeum and the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Moses Michael Hays died in 1805. His obituaries in the secular press remembered him as “a most valuable citizen . . . now secure in the bosom of his Father and our Father, of his God and our God.” Hays lived his life successfully as an American and a Jew, accepted by the Boston community with respect as both.”[19]

Three years after their father Isaac died in Jamaica, the Touro children’s mother died in 1787. The children remained and grew up in their uncle’s house. The experience left an indelible mark on Judah. He had a home at his Uncle’s table but he was an orphan. He was part of the family yet he was not. Judah was nine years old when his father died. He was twelve years old when his mother died.

Moses Michael Hays looked after his two nephews and niece. He taught them about business and the necessity of a good reputation with strong reliable relationships. They grew up learning the importance of charity and how it could enhance business and community standing. No doubt he introduced them to the universalism of Scottish Rite Freemasonry as well. Freemasonry’s basic tenets were:

Brotherly love: Love for each other and for all mankind Relief: Charity for others and mutual aid for fellow Masons

Truth: Only a man’s individual faith and his relationship to God can provide the answer to universal questions of morality and the salvation of the soul.[20]

None of the basic tenets of Freemasonry seemed at odds with Hays’ Judaism. The lessons were learned by the Touro children and were applied by them in life. [21]

“Judah Touro thus was reared in the very cradle of American liberty. His personal intimacy with eminent non-Jews broadened his horizon, and led him to respect the beliefs of others and to assist the cause of charity for all alike. He learned that one could be a devout Jew, and yet mingle freely and easily with his Christian brethren, teaching them to respect his faith, while at the same time respecting theirs.”[22]

“In his uncle’s home he had grown up with his cousin Catherine. They had fallen deeply in love with each other, and, had they married, they would both have been happy. Judah Touro would doubtless have become a successful Boston merchant, though he would probably never have attained the great national reputation by which he is remembered today.

While Moses Hays had a high regard for his nephew’s character and ability, he was unalterably opposed to their marriage because they were cousins, and all efforts to overcome this prejudice were in vain.

It was probably due to his desire to separate the lovers and to break up this attachment that, in 1798, Hays sent his nephew as supercargo in connection with a valuable shipment he was then making to the Mediterranean. As Touro was about twenty-three at the time and his cousin Catherine a year younger, and as the trip was like to be a long one, Mr. Hays doubtless believed that each of them would form new associations in the mean time and that their infatuation would eventually disappear.

The voyage on which Touro embarked was an extremely hazardous one in that day, owing to the wars of the first Napoleon. While on its way the ship was attacked by a French privateer, but Touro displayed considerable courage during the conflict and finally succeeded in landing his cargo safely. At length he returned to Boston with the profits of the enterprise and with high hopes that his uncle would now relent, so that his lover’s dream would finally be realized. “[23]

The love that Judah had for Catherine and she for him only intensified while he was gone. It soon became quite clear to Moses Michael Hays that the only way to end the relationship was to separate them for good. Two years after returning from his successful business assignment by his uncle to the Mediterranean, Moses suddenly, unexpectedly and forcefully discharged Judah from his family business. He ordered him out of his house. He forbade his daughter Catherine from ever having any contact with Judah again.

Judah departed. He was virtually penniless. He went to Boston to find work and be relatively close to Catherine. No matter how he tried, his best efforts to contact her failed. Judah was embittered but determined to show his uncle that he was not a failure that could be brushed aside.. He would make his fortune. Judah Touro did just that. He never communicated with Catherine again nor she with him. Judah Touro never married nor did Catherine.

Judah was twenty six when he left Boston in October of 1801 heading for the opportunities he heard about in New Orleans. During the voyage, he was robbed of all his money, $100. The ship stopped in Havana, Cuba. Touro, determined, disembarked and found work. He saved enough money to continue to his voyage to New Orleans. He arrived in the Spanish controlled city in February of 1802. It was a city of 8,000 people, more mud and bustle than city. Commerce down the Ohio River from the American interior and joining with the ‘’father of waters – the Mississippi” was just developing. He had arrived at the right place at the right time. The port of New Orleans was alive with activity and possibility.

Judah Touro’s reputation was formed in Boston. The contacts he established there trusted him as their factor, as their agent to sell their goods in New Orleans for a honest profit. Touro earned a commission on each consignment. He worked harder than anyone around him and did so with a key eye to keeping his relationships clean and his books honest and fair. His business quickly grew and grew.

President Thomas Jefferson boldly purchased the entire Louisiana country from France who had succeeded in ownership after Spain of the vast territory. With the single stroke of a pen, the “Louisiana Purchase -1803”, more than doubled the land mass f the United States. American control of New Orleans brought massive American migration to the Louisiana territory. Many would be businessmen arrived in New Orleans with dreams, hopes and sometimes less than honest scruples. Many fortunes were lost to uncontrolled thieving and dishonest writhing in New Orleans.

Honesty, trustworthiness, reliability were virtues hard to come by. Touro’s business boomed.

Pastor Theodor Clapp wrote in his memoirs about Judah Touro.

“Through all these times which tried men’s souls, Touro pursued the even tenor of his way, calm, self –possessed and with his robes unstained. The poisonous breath of calumny never breathed upon his fair name as a merchant, the most tempting opportunities of gain from the shattered fortunes which were floating around, not in a single instance caused him to swerve from the path of plain, straight forward, lofty, unbending, simple and magnanimous rectitude.”[24]

Touro opened a small business that soon became a large business. He expanded from simply factoring for a commission to direct retailing and importing Northern good using his network of Northern business associates. Instead of putting his cargos on ships headed to distant ports Touro soon owned the ships. The profits from his ventures he reinvested back into his business. Touro regularly purchased land in and around New Orleans for cash. He only bought what he could pay for in full. He was the first to open his business for the day and he was the last to close. He worked hard and lived very modestly.

As his wealth built he did not use it to live ostentatiously. His personal habits were modest and unassuming. If he entertained guests he ate sparingly, modestly reserving the best food and wine for his guests. The rich foods of New Orleans, the cream sauces, meats and shell fish were not a staple of his diet. He ate simply. He ate almost as if in respect for the Jewish kashrut laws by avoiding the local culinary offerings.

His personal life was private and modest which became reclusive as he became older. He was awkward, uncomfortable with the ladies of New Orleans. The Jewish community was very small while he was still a young eligible bachelor. There were not a large number of eligible Jewish young ladies in the city. He chose to remain a solitary individual. He always knew what was going on but he never was very interested in socializing.

Judah Touro’s closest friends were two brothers, James H. and Rezin Davis Shepherd. They had arrived shortly after Touro had to New Orleans. The Shepherds were from an old patrician Virginia stock. The men quickly became business associates. The Shepherds were Freemasons and with Touro, quite possibly a Freemason himself, the connections and trust were automatic. Rezin Davis Shepherd was on the board of directors of the Bank of New Orleans. Touro probably invested in it.

New Orleans and the United States are thousands of miles from Europe. President George Washington had warned against European entanglements. Americans felt secure far away from Europe as the Napoleonic wars assumed wider and wider reach. It was delusion to believe that a great ocean could act as an impenetrable watery shield for America against the madness of European wars. America was drawn into the world struggle between Britain and France.

The American War of 1812: Britain invaded, burned the capital city of Washington and caused havoc with American commerce. The key to destroying the American economy was to destroy and control her assets. New Orleans was one of the most important cities in the United States. More importantly, New Orleans controlled the mouth of the Mississippi River and in turn the entire commerce of the interior of the United States. The British sent a major invasion fleet packed with crack troops from the recent defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte to take New Orleans. It was late 1814. The American forces were a rag tag collection of regular army, misfits, frontiersman, farmers, pirates, slaves, Indians, free black men, mulatoes and native French creoles. The army of 6,000 men was assembled under a Tennessee back woods general and Indian fighter – Andrew Jackson. They were to face 16,000 of the finest, battle hardened British Continental troops under Sir John Packenham. The odds against the Americans were very, very bad.

Judah Touro volunteered to defend his country. He was nearly forty years old.\

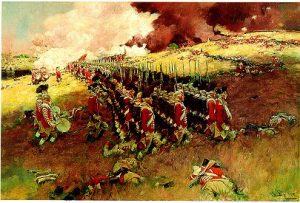

Battle of New Orleans

“When the War of 1812 broke out, Touro was already one of the foremost merchants in Louisiana. His early training as well as his associations during the years spent in Boston had instilled in him that staunch American patriotism which puts love of country above all other interests in time of danger. When, therefore, Sir John Packenham besieged New Orleans, Touro at once put aside his large business interests, joined the militia, and like a true patriot took part in the defense of the city under General Andrew Jackson. Despite his great wealth, no service in the interests of his country seemed too humble.

In his Life of Andrew Jackson, James Parton, the historian, quotes with approval the following statement of another contemporary writer:

Judah Touro, the far famed and far beloved philanthropist of New Orleans, on this day (January 1, 1815) served his country in a capacity much more dangerous than that of combatant. When the state was invaded, Mr. Touro was attached to the regiment of Louisiana militia… After performing severe labors as a common soldier in the ranks, Mr. Touro on the first of January volunteered his services to aid in carrying shot and shell from the magazine to Humphrey’s battery. In this humble but perilous duty he was seen actively engaged during the terrible cannonade with which the British opened the day, regardless of the cloud of iron missiles which flew around him and which made many of the stoutest hearted cling closely to the embankment or seek some shelter. But in the discharge of duty this good man knew no fear and perceived no danger. It was while thus engaged that he was struck in the thigh by a twelve pound shot which produced a ghastly and dangerous wound.”[25]

Touro was carried off the field. A physician looked at the wound and simply made Touro as comfortable as possible. He was being given up for dead.

The news of Touro’s battlefield injury, and the death sentence pronounced upon him by Dr. Kerr, reached Rezin Davis Shepherd. Rezin was originally attached to Captain Ogden’s Horse Troop. “Fortune had it so, that Shepherd became the aide of Commodore Pattterson, and was assisting him to erect his battery on the right bank of the river, in defense of the city. While engaged in this task, Shepherd crossed the river to procure two masons to do some work on the Commodore’s battery. … The first person Shepherd saw on reaching the other side of the river told him of the condition of Touro. He was shocked. Shepherd ‘rushed to the place where Touro was lying. It was near a wall of an old building, in the rear of Jackson’s headquarters. Dr. Kerr, who was dressing Touro’s wounds, shook his head, indicating that there was no hope for Touro.” [26] Shepherd refused to accept the doctor’s decision. He commandeered a cart and brought Judah back to his home. Rezin refused to stand by and let his friend simply die. For a full year Touro lay in a bed of agony and pain. Shepherd hired nurses, attendants and personally assisted his injured friend. Judah Touro survived. Touro never forgot the selfless act of his friend.

Judah Touro remembered his lessons from Moses Michael Hays. He always remembered the values that Hays spoke of as a Jew and as a Freemason. Charity and charitable efforts were always selflessly on Touro’s mind.

Abraham Touro, Judah’s older brother died tragically October of 1822. His will left large bequests to the State of Rhode Island to preserve the synagogue in Newport, large bequests to various charities, hospitals, alms houses, asylums for impoverished women and young boys. He even left a bequest to the humane society. Thinking also of his own family, Abraham Touro left $100,000, a very large sum in 1823, to his brother Judah. Judah never used a penny of the money for his own benefit, instead choosing to donate the entire sum to charity. When his sister Rebecca Lopez died in 1833, again he was willed $80,000. Again Judah chose to give the money to various charities.

Judah Touro’s charitable efforts where done quietly, frequently without the beneficiary knowing he was going to do it or why.

In 1823, the First Congregational Church of New Orleans was in great financial difficulty. Their church was in danger of being foreclosed leaving the worshipers with no House of God to pray in. Touro purchased the building located in a very fashionable part of town where the property values were going up and up by outbidding the highest bidder for the location. It was understood that the structure could be torn down and the rebuilt on for a considerable profit to the new owner. Touro paid $20,000 for the property. Grumblings were heard at the auction about the Jew’s actions. Touro though, immediately turned around and gave the keys back to the Congregation led by the Rev. Theodore Clapp, the first Unitarian Minister in New Orleans.

Years later, Rev. Clapp wrote about the incident:

“Mr. Touro became the purchaser without any conditions expressed or implied as to what disposition he would make of it. Then we were few, feeble, impoverished, bankrupt. A noble Israelite snatched us from the jaws of destruction. From that day up to its conflagration (the church burned in 1849) he held it for our use, receiving not enough in the way of compensation for keeping it in repair. He might have torn the church down and reared on the site a block of stores whose income by this time would have amounted to half a million. He was urged to do so, and at once replied to a gentleman who made a very liberal offer for the property, that there was not money enough in the world to buy it… Immediately after its destruction,(1849) he bought a new building for us, where we have worshipped till now, free of charge. Is there a Christian society in New Orleans that has ever offered to help us?

This church subsequently became one of the foremost in Louisiana, but the noble action of Judah Touro was never forgotten…..At an elaborate celebration in February, 1933, when both the distinguished speakers of the occasion, as well as the public press paid glowing tribute to Touro’s generosity…….

With all this, however, Touro always remained an observant Jew. Though he helped the church mentioned above, we are told he never entered it, and though its pastor was his friend, he never heard him preach. This was not due to any narrow scruple, for Dr. Clapp relates that he had often heard Touro say that ‘he would like to see all churches flourish in their respective ways, and that was heartily sorry that they did not more generally fraternize with love, and help each other.” [27]

There are numerous anecdotes of Touro’s generosity to complete strangers. A poor woman once approached him and told him of her troubles. She was a mother, penniless, with small children. Her rent was due and she had no money for rent, not even funds for food or clothing. Before she had even finished her story, Touro had written out a bank draft for her for $1,500, even sending his clerk to be sure that the bank paid the indigent woman. Years after Touro had passed away, the woman publically revealed that Touro’s act of generosity saved her and her children. They were able to get back on their feet. He had saved their lives.

Touro stayed late at his office every day. One evening a drunk passed his door being taken to debtor’s prison by the sheriff. He had known the family once under different circumstances. Inquiring of the amount of money the man owed, Touro paid the $900. When asked about his actions Touro responded, “I do not expect much that it will be of any benefit to the individual himself, but I performed the act for the sake of his family.”[28]

Educational opportunity was important to Touro. “In 1824, a small group of prominent citizens of New Orleans formed a Free Library Society “for the purpose of extending knowledge and promoting virtue among the inhabitants of the city.” Judah Touro at once offered to put up the library at his own expense.”[29] The community named the library the Touro Free Library of New Orleans. It was the only public library in the city for years.

Touro, in a number of instances, assisted young people with their educational expenses. In his later years he created an endowment at the University of Louisiana to recognize outstanding scholarship. 1884, the University of Louisiana was renamed Tulane University. The Touro award is an annual Gold medal prize.

After another major outbreak of deadly Yellow Fever in New Orleans, Touro created and funded the largest free hospital in Louisiana, the Touro Infirmary.

Judah Touro did not neglect his own community of faith with his generosity.

Jacob Solis arrived in New Orleans in 1827. The high holidays were approaching and he wished to find a place to pray. New Orleans had about 100 Jews in the city. There was no Synagogue, no permanent Jewish house of Worship in New Orleans for the State of Louisiana. Solis decided to do something about it. Solis founded Congregation Shangarai Chassed (Gates of Mercy)[30] which was officially chartered by the State as the first permanent Jewish house of worship in Louisiana, December 20, 1827. A small building was purchased and the synagogue community was organized with German Ashkenazic traditions. Touro was approached to contribute to the new congregation which he did even though he was of Sephardic background. Touro did not attend services at Gates of Mercy. Manis Jacobs, with no religious training, was the first rabbi until his death in 1839. Touro had provided some financial assistance to the German synagogue but it was not the house of God with which he chose to associate.

Gershom Kursheedt

Rev. Isaac Leeser

“Born in 1817 in Richmond, Virginia, Gershom Kursheedt had a distinguished Jewish pedigree. His grandfather was the first American-born rabbi, Gershom Mendes Seixas of New York, and his parents were Rabbi Israel Baer Kursheedt and Sarah Abigail, daughter of Gershom Mendes Seixas. The seventh of Israel Baer and Sarah Abigail’s nine children, Gershom is reported to have absorbed “a passionate love of Jewish learning and a profound concern for Jewish causes” from both his parents. He was challenged to put both of these commitments to work when he moved to New Orleans at age 21 to work in an uncle’s retail business.”[31]

“Bringing to New Orleans a profound love of his faith, Gershom no doubt looked forward to joining Louisiana’s sole Jewish congregation, Shanarai-Chasset, and become a part of a vibrant Jewish community. What hopes he harbored were soon dashed by the dismal state of Jewish life in New Orleans at the time. Though in existence for over a decade, Shanarai-Chasset still lacked a sufficient number of prayer books for services. Nor was there a shofar or Torah scroll. Services followed no set pattern, with some participants employing the Sephardic minhag, others the Polish or German minhag, and still others the English minhag. The result was catastrophic.” [32]

Albert J. “Roley” Marks was Shangarai-Chasset’s “Rabbi” when Kursheedt arrived. When Marks died in 1842, the German periodical Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenstums (General Journal of Judaism) wrote about him and indirectly about the quality of Jewish life in New Orleans.

“This is a rabbi? This stigma in the ranks of the Jewish ministry eats whatever comes before his maw, never keeps the feast of Passover; indeed has had none of his boys circumcised. In addition to his post as rabbi, Mr. Marks – that is his name – holds a job as an actor at the American Theatre and that of chief of one of the fire engines. At Purim, the book of Esther could not be read since, so the President of the Congregation informed the minyan, the rabbi/reader was preoccupied with his duties as fire chief. When challenged by a pious member of the congregation, the rabbi, beside himself with wrath, pounded the pulpit and shouted: “By Jesus Christ, I have a right to pray!” After his death the rabbi’s widow, a Catholic, was restrained only with difficulty from putting a crucifix in his grave.” [33]

Having been raised in the Sephardic tradition and unable to tolerate the seeming dysfunctional German Jewish Gates of Mercy as a legitimate Jewish house of prayer, Kursheedt had had enough.

Kursheedt planned carefully. He used his family connections to get an introduction to Judah Touro. Touro had met his father when he was in Boston.

“In 1844, in his first major step toward redefining Judaism in New Orleans, Gershom, following his father’s and grandfather’s example in New York, was instrumental in organizing New Orleans’s first Hebrew Benevolent Society, a predecessor of the Jewish Federation.

Kursheedt approached Touro to help fund the Benevolent Society which Touro did.

In 1845, Gershom persuaded forty Jews to join with him in establishing New Orleans’s second synagogue, Nefutzoth Yehudah (Disbursed of Judah). Gershom was Nefutzoth Yehudah’s first president……Nefutzoth Yehudah adopted the Sephardic minhag.”

Kursheedt wanted to manipulate Touro, not only the city’s but one of the richest men in the United States. He deliberately chose a tradition of worship that would appeal to Touro, the Sephardic minhag, even though the vast majority of Jewish immigration to New Orleans was increasingly Ashkenazic. He deliberately named the new synagogue Nefutzoth Yehudah (Disbursed of Judah) after Judah Touro to appeal to what Kursheedt believed was his vanity.

Nefuzoth Yehuda (Knights of Columbus Hall today)

Kursheedt, “With the help of an Episcopalian friend of Touro’s, Rezin Davis Shepherd, Gershom persuaded Touro to purchase an unused neoclassic Episcopal church on Canal and bourbon Streets and remodel it into a 470- seat sanctuary.”

Kursheedt felt he had persuaded the “old man” to do what he wanted him to do. Touro was seventy years old at that time. Kursheedt was 28. Touro rarely acted without careful thought and consideration. He was no fool. He built his fortune by hard work, logic and appropriate risk taking. He evaluated goals and purpose. Once he was convinced of the rightness of a project he acted fully. Kursheedt did not convince Judah Touro to be a Jew again. Touro and his family had been involved in Jewish life and Jewish charitable giving for decades. Touro was not a rabbi, he was not a Jewish evangelist. He was a businessman who was very willing to give and support projects both Jewish and non that would advance the values he believed in. Once a viable Jewish alternative existed in New Orleans, he thought about it, he considered it, and he acted fully. Touro focused on Nefutzot Yehudah.

No detail of involvement was too small for Judah in the construction of the synagogue. “No expense was spared. The cedars of Lebanon that comprised the original pillar of the Aron Hakodesh (Ark of the Covenant) was shipped on one of Touro’s vessels. [34]

Kursheedt needed to work with Touro whose money and good will he desperately needed. At times the impetuosity of the young man could not understand the deliberateness and meticulous attention to detail of the older man. It was the attention to detail that made Touro successful. Kursheedt’s goals were admirable but his attitude and his impetuosity became privately abusive and borderline contemptuous.

Kursheedt wrote privately to Isaac Leeser the editor of the Occident and American Jewish Advocate complaining about Touro. Kursheedt seems to have forgotten whose hard earned money he was spending.

“Dec. 18, 5608 (1847)

“Mr. Touro is the very impersonation of a snail, not to say of a crab whose progress (to use a paradox) is usually backward. My patience is well nigh exhausted with him and I am interrogated by so many concerning his intentions that it is not unusual for me to dodge a corner in order to avoid meeting certain parties who seem to think that I am making a mystery of the matter… Your advice… to urge Mr. Touro is… very good and I have profited from your council but the only answer I get is “well, we will see,” and “there is enough time.” I cannot order the man… I must be very careful to humor him or in one instant all will be lost….”[35]

Leeser too had his own personal disparaging opinion of Judah Touro.

“Mr. T. was not a man of brilliant mind; on the contrary, he was slow, and not given to bursts of enthusiasm, as little as he was fond of hazardous speculations; and he used to say that he could only be said to have saved a fortune by strict economy, while others had spent one by their liberal expenditures … he had no tastes for the wasteful outlay of means on enjoyments which he had no relish for. He [had] thus the best wines always by him, without drinking them himself; his table, whatever delicacies it bore, had only plain and simple food for him. …”[36]

“April 13, 5608 (1848)

“Since I lately addressed you I have been very much bothered with… setting estimates for finishing the inside of the synagogue. After I had closed the contract, Mr. Touro kicked at certain alterations in the building till I decided to give them up. I am worried half to death by the members of the congregation on the one hand and the mechanics on the other: a perfect scapegoat to bear the brunt of all.”[37]

“January 1, 5609 (1849)

When I was about to write to you, I discovered that the ceiling of the building was so defective as to be really dangerous and after some weeks lost in convincing Mr. Touro of this he acceded to my wish to have it taken down. For seven weeks past we have had incessant rains and therefore could not plaster. The appearance of the cholera (which I am happy to say is now in the decline) made workmen very scarce. And now I think we cannot consecrate the building before March or April. I hope ere many days that Mr. Touro will tell me to order out what we require. But he is dreadfully slow and the concern has cost him so much already that he is perhaps to be excused for holding back… Yet all will come right at last.”[38]

Judah Touro remained actively and intimately involved in almost every detail of the synagogue’s construction and religious ornamentation. In a letter to Leeser, May 2, 1849, Kursheedt refers in detail to the furniture for the new synagogue, and how Touro was taking care of the matter.

A year later, the synagogue was ready.

“The beautiful synagogue which Touro presented to the Spanish and Portuguese congregation was consecrated on May 14, 1850. A contemporary account of that ceremony throws additional light on Touro’s character. After mentioning that the silver ornaments and silk mantels for the Scrolls of the Law had been made in Philadelphia at the direction of Mr. Touro, the account states that a stone had been prepared with a Hebrew inscription to the effect that the building had been donated by Judah Touro to the Portuguese congregation as place of prayer: “In testimony of which this stone is solemnly deposited beneath the portals through which the faithful are to enter to praise the Lord. New Orleans, 3 Sivan, 14th May, 5610, and the 74th year of the Independence of America.” The account then proceeds:

Owing to the well known character of Mr. Touro who is averse to all ostentation, the number present at this interesting occasion was limited to about ten persons, when it would have been an easy thing to have a numerous attendance to witness the final and solemn transfer of all the highly valued property constituting the synagogue and its appurtenances for the use of the Congregation by the donor. About half past ten of the above date, everything being in readiness, Mr. Touro with his own hands applied the requisite mortar beneath the memorial stone and when it was properly adjusted, it was covered with a slate slab and the flooring was then replaced over all…. About half past five P.M. the ceremony of solemnly dedicating took place in the presence of a very numerous attendance of Jews and Gentiles.

The dedication sermon was preached by the Rev. M.N. Nathan, who invoked the blessing of Almighty God upon the United States of America, but who, probably at Touro’s request, made no mention whatever either of the gift or the donor.”[39]

A year later Touro erected a substantial schoolhouse on the lot adjoining the synagogue.

The Jewish community failed to give the financial support that the synagogue required. Rabbi Nathan wrote to Leeser, January 9, 1853:

“The folks here are very willing to employ the best minister possible, but the truth is, they don’t want to pay. They would like Mr. Touro to do that duty….. He (Touro) is heartily tired of this continued drain on his purse, and I will no longer submit to be a pensioner on his bounty… since my engagement in February, 1850, he has paid nearly two-thirds of my salary.”[40]

Judah Touro continued to support the synagogue and the community until the day he died. In death a substantial bequest was given to them.

Probably unknown to Kursheedt and Leeser, against the local issue of the construction of the synagogue, Judah Touro had been engaged in secret negotiations that would affect the American national character. Kursheedt and Leeser would probably not have cared as much about it, but Judah Touro did.

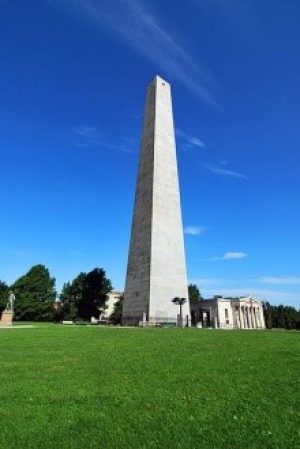

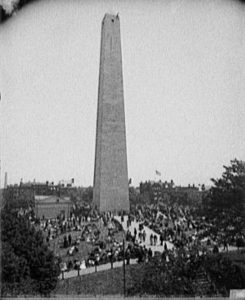

In the annals of American revolutionary history various sites were factually the struggle against British oppression. Many places of struggle come to mind, Lexington/Concorde, Bunker Hill, Valley Forge, Trenton, Yorktown to mention a few. Touro was fond of making note that he was born when the guns were roaring at Bunker Hill. To Touro, and to many Americans, Bunker Hill was the first great battle of the war. It was remembered and revered with passion.

No less a personage than the Marquis de Lafayette, laid the cornerstone (1826) in Boston for what was planned to become, the Bunker Hill National monument. Fourteen years later the monument remained unfinished for lack of funds, even after Amos Lawrence of Boston offered a challenge grant in 1839. Lawrence would give $10,000 toward the completion of the memorial but the public had to raise the balance, the remaining $10,000. There was no response from the public despite appeals from of America’s greatest orators and leaders of the day, Edward Everett and Daniel Webster.

Bunker Hill Monument

2005

Battle of Bunker Hill

Bunker Hill Monument

1890

“The matter was brought to Touro’s attention in far-off New Orleans and he was immediately interested. He had always been proud of the fact that he had been born on the eve of the great battle, and his spirit of patriotism was aroused. He at once contributed the remaining $10,000, but with the injunction that the donor’s name should remain anonymous. Despite this, however, the fact became public and the announcement that the funds were at last available was the occasion of general rejoicing throughout the country. When the finished monument was dedicated, on June 17, 1843, in the presence of the President of the United States, with Daniel Webster as the orator of the occasion, the generosity of Lawrence and Touro was recalled at Faneuil Hall in the following lines which are generally attributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes, and which have since become famous:

Amos and Judah – venerated names,

Patriarch and prophet press their equal claims,

Like generous coursers running “neck to neck”,

Each aids the work by giving it a check,

Christian and Jew, they carry out one plan,

For though of different faith, each is in heart a Man

The newspaper accounts of the Bunker Hill Dinner at Faneuil Hall, which followed the dedication, mentioned the fact that the names of Lawrence and Touro were placed over the front platform under the eagle.”[41]

Late in 1853 Judah Touro knew that his body had begun to fail him. He had to prepare to separate himself from his short earthy existence. He knew it would be eternity and God he to answer to shortly. It was necessary to order his affairs. He had to write his will. Touro’s mind, sharp, clear, resolute in his values and beliefs, turned to the attention of the final details he had to face.

Gerhsom Kursheedt became very concerned. There were no heirs to Touro. There was an immense sum of money at stake that he could direct to benefit the Jewish people. It was an opportunity. It was a necessity that he felt he had to focus on. He had to shape the old man’s mind and the disposition of his will. Kursheedt had to keep a warm smiling face, hiding his true feelings as ever he worked. Touro had been no fool all his life. He no doubt knew how to read men and their motives but it was the close of his time. He would need the good will of those who came after him. His friend Rezin Davis Shepherd remained the closest person to his living soul. Rezin had moved back to his home in Shepherdstown, Va. (W.Va.). A much younger relative of Shepherd’s lived in New Orleans and was by Touro’s side. As much, as trusted and loved as Rezin Shepherd was by naming his an executor of his will, he needed to fulfill the second side of his life- his Jewish side. He needed Kursheedt. Kursheedt probably never understood this about Touro. Touro remained an object to achieve his goals of growing, reinforcing and preserving Jewish life.

Kursheedt never understood the personal trauma of Touro, the impoverished orphan growing up in his uncle’s house but never good enough for his daughter. He never understood Touro’s personal pain. Kursheedt never understood Touro’s pain being banished from his uncle’s home and forbidden the most deeply mortal dream he had and loved, Catherine Hays. Touro felt the pain of others and did what he could instinctively to help them.

He provided for schools. He helped without being asked. The repeated bequests in Touro’s will to help the orphan, the widow, the poor, the dejected of life, without regard if they were Christian or Jew no doubt distressed Kursheedt.

After Touro’s death, Kursheedt wrote to Isaac Leeser about his struggles with Touro to direct Touro’s money and secure money for Leeser’s interests in particular. Though a Freemason his motives were not consistent with Freemasonry’s. His motives were deeply personal.

“Oh my dear friend, if you knew how I had to work to get that will made… you would pity me… Arguments, changes and counter changes in the sums for institutions, till my heart sickened. I appeared calm, but indeed was almost crazy, ever dreading that nothing would be achieved in the end. The list of Jewish institutions, I made up as well as I could. I had dreadful hard word to raise your Education Society from 10 to 20,000 ($)[42]

Judah Touro’s breath gently ended at 11:o’clock Wednesday morning January 16, 1854.

The entire city went into deep morning for him. His eulogies, his attestations of humanity and generosity, flooded the South. They soon spread around the United States.

Touro had lived almost his entire life in New Orleans. His desire in death was to return to his beloved family who he had so missed the fifty years of his being away. Unbeknownst to Touro, Catherine Hays, the love from his youth to whom he left a bequest in his will, had passed away sixteen days before he. Like Judah, Catherine had never married.

According to his will his mortal remains were brought to Newport for interment. When his body arrived in Newport on the streamer Empire City, June 6, 1854, “it was conveyed to the synagogue and placed before the Reading Desk where the father of the deceased had stood as Hazan – minister – more than eighty years before.

On the coffin two candles burned until the funeral service was over.

Among the Newport City Documents is to be found the exact record of this funeral. It is the work of an eye witness; let it speak for itself:

The funeral of the late Judah Touro was solemnized the same afternoon; the procession was the longest which has been seen here for many years. The streets were crowded with people, the stores all closed, and the bells tolled. About one hundred and fifty Jews were present from various parts of the country.

The city council assembled at the City Hall, and marched in procession to the Synagogue, the gallery of which was already densely crowded with ladies, and there were thousands on the street who could not gain admission. The coffin stood in front of the reading desk.

Soon after the arrival of the City Government, the Rabbis and other Jews came in procession, the former taking seats in the desk. As soon as the synagogue was filled, the doors were closed, and thousands remained outside, until the ceremonies were concluded.

The services were conducted by the Rev. J.K. Guthein, of New Orleans in Hebrew and English. I this address, which was excellent, he paid eloquent tribute to the memory of the departed.

Rev. Isaac Leeser spoke after Guthein:

If you had seen him in his daily walks, you would not have suspected him to be the man of wealth and the honored protector of the poor, as he was: the exterior of our brother betrayed not the man within. But when he gave you his hand, when he expressed in his simple manner that you were welcome, you could not doubt his sincerity; you were convinced that he was emphatically a man of truth, of sincere benevolence. And thus he lived for many years, unknown to the masses, but felt within the circle where his character could display itself without ostentation and obtrusiveness, at a period when but a few of his faith were residents of the same city with him….

If you have ever been present during the hours of worship, you may have observed a plainly-dressed old man, seated in a corner in the upper section of the synagogue, devoutly engaged in prayers, not throwing about his eyes to the right or to the left, but feeling, as far as a man might judge from the manner he exhibited, as an humble mortal in the presence of his Creator; and all he ever received was the office of opening the ark where the testimony is deposited before the reading of the law.

“At the conclusion of the services, at the synagogue, the procession was formed in the order: – Rabbis and Jews from abroad; city Marshal; Mayor; city Sargeant: President of Common council; Common Council; Redwood Library; Corporation; preceded by the President and Directors; Protective company No. 5; Citizens and strangers.

It moved through the streets as previously announced, to the cemetery, where the remains were consigned to their native dust. The Rev. Mr. Leeser delivered a very appropriate and eloquent address. After the coffin was deposited in the grave, the Rev. Mr. Isaacs deposited upon it a quantity of earth which was brought from Jerusalem for the purpose, at the same time uttering a few appropriate remarks. Prayers were then offered at the graves of the members of the family.

As the procession of the funeral moved from the synagogue to the cemetery the bells of all the churches tolled and the places of business generally closed.”[43]

Judah Touro sleeps amidst his family members in the Newport Jewish Cemetery. His tombstone reads:

“To the Memory of

Judah Touro

Born Newport, R.I., June 16, 1775

Died New Orleans, La. Jan. 18, 1854

Interred here, June 6

“The last of his name

He inscribed it in the Book of

Philanthropy

To be remembered forever”

Touro family burial ground

Fifteen feet away from Judah’s grave is a smaller, much simpler stone. On it is inscribed simply:

“To the memory of Catherine Hays.”

Judah Touro’s will was probated in New Orleans. His estate was estimated in excess of a half million dollars. The estate, in 1854, was so immense that it easily made Judah Touro one of the ten wealthiest men in the United States. It was extraordinary in that he willed it all to charity. His bequests were three hundred thousand dollars to Christian and public institutions. The rest he willed to Jewish needs.

Gershom Kursheedt acted immediately to fulfill one important part of the will. Touro had asked that his money be used by Sir Moses Montefiore[44] to better the conditions of the Jewish people in Jerusalem.

Judah Touro’s will:

“ It being my earnest wish to co-operate with the said Sir Moses Montefiore of London, Great Britain, in endeavoring to ameliorate the condition of our unfortunate Jewish Brethren, in the Holy Land, and to secure to them the inestimable privilege of worshipping the Almighty according to our religion without molestation. I therefore bequeath the sum of fifty thousand dollars.”

Kursheetdt immediately contacted Sir Moses in London.

Sir Moses Montefiore

From Sir Moses Montefiore’s diaries:

“Mr. Gershom Kursheedt, one of the executors of the late Juda Touro of New Orleans, arrived to arrange with Sir Moses about the legacy of $50,000 left at his disposal for the purpose of relieving the poor Israelites in the Holy Land in such manner as Sir Moses should advise.

Sir Moses, at the first interview he had with this gentleman, suggested that the money should be employed in building a hospital in Jerusalem. Mr. Kursheedt immediately assented and Sir Moses immediately gave him the plan and drawing made about a year before and he said that the thing was done. He was most happy, as it settled the principal business he had in England, the co-executors (having) given him full power to agree to any plan Sir Moses should propose. A letter was prepared by a solicitor to that effect, which Mr. Kursheedt signed. ”[45]

Gershom Kursheedt has a few weeks to think over his duties and responsibilities to Judah Touro before the agreement was to be finalized. Judah would have been intimately involved in the details and planning. Kursheedt walked in and was handed a pre-planned hospital idea by Montefiore. He was uncomfortable with the situation.

August 15, 1854, he was supposed to finalize the transfer of funds, completing his executor duties for Judah Touro with Moses Montefiore. Kursheedt realized that by finalizing the agreement he would not be able to oversee his responsibility. He would no longer be directly involved with the improvement of the Jewish condition in Palestine.

“Sir Moses, however, had soon to learn that Mr. Kursheedt had been induced to alter his mind, and had withdrawn the consent he had given to the building of a hospital. The 15th of august, it appears, had been fixed by sir Moses for communicating the consent of Mr. Kursheedt to the American consul in London, but at the appointed hour, when Sir Moses met Mr. Kursheedt at the Alliance, the latter, to Sir Moses’ great surprise, said that he must decline gong with him to the American Consul, and could not sign the proposed memorandum.”[46]

Kursheedt chose to continue working under Sir Moses Montefiore’s guidance to comply with Judah Touro’s will but maintained control of the money. Letters of inquiry were sent to the Rothschild’s for support and assistance in the project. Kursheedt returned to New Orleans only to be called back to London, April 25, 1855, to join Sir Moses for a trip to Palestine to look into the hospital idea.

The trip was very successful. A location for the hospital was identified. Kursheedt was very impressed with Sir Moses but more so with how he was received, as if by royalty, by the Jews of Jerusalem and Hebron. It affected him.

“The Jews here are making great preparations at the synagogue to receive Sir M M in style. Many of the consuls and conspicuous citizens here have paid their visits. I feel quite like a nobleman myself now, although I am not the less wedded to Republican institutions.” [47]

Kursheedt returned to New Orleans, arriving home November 1855. He quickly learned that the hospital idea would not work out because of a competing hospital project by the Rothschilds.

Sir Moses wrote to Kursheedt in April, 1856. He knew that Kursheedt controlled a great deal of money that could be used for the Jewish community in Palestine. “It must be a great happiness to you to know, that with your great influence with the late Mr. Touro, Peace to his Soul, you have been the means of directing the eyes and hearts of many of our Brethren towards the Holy Land and contributing to the welfare of our coreligionists now dwelling in that land of our fathers.”[48]

1857, Kursheedt returned to England and joined Sir Moses on another trip to Palestine.

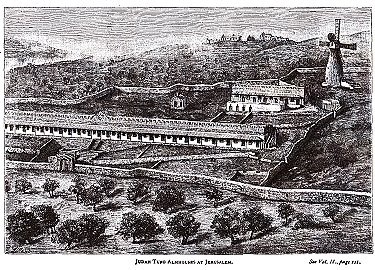

The proposal for Judah Touro’s bequest had changed. Sir Moses proposed, with the concurrence of the Rabbis in Jerusalem, the creation of an almshouse outside of the Old City Walls. Health and living conditions within the Old City had deteriorated significantly. Poor sanitation, housing and health were real concerns. The proposal would be the first Jewish settlement outside of the Old City Walls.

It was a major departure and risk for the Jewish community. Armed roving bands of Bedouin ranged freely outside the City walls attacking, robbing and murdering travelers. Wild animals roamed the hills. The Rabbis were concerned that settlement outside of the walls would result in apostasy and religious difficulty in observing Jewish traditions.

For Kursheedt the idea of an almshouse, using Touro’s money was logical. A bequest of Touro’s will was the creation of the first major public almshouse in the United States in New Orleans.

Kursheedt’s relationship with the Montefiore’s had developed warmly, comfortably over the years. Sir Moses wrote to Kursheedt, July 8, 1858, suggesting he come and stay with them while they decided how to handle Judah Touro’s bequest. Kursheedt returned to Europe in 1859.

The sudden traumatic distraction of the Mortara[49] Affair diverted Sir Moses’ attention. Kursheedt returned to New Orleans. A year later, (July, 1860), he was once again with Sir Moses. Meeting with the Chief Rabbi of England, Nathan Marcus Adler in Brighton, a resort on the English Channel, they agreed on the project. The funds were transferred to Sir Moses. They renamed the Judah Touro almshouse project, Mishkanot Shaanaim[50], The Dwellings of Those That Are at Ease, to “avoid hurting the feelings of the inmates by calling the buildings almshouse.” [51]

Judah Touro Almshouse (Mishkanot Shaanaim)[52]

Life was good for Gershom Kursheedt with the Montefiores. On January 12, 1861 he married Sir Moses’ niece Grace Guedalla. Tragically, two years later, 1863, Gershom Kursheedt suddenly died. He was 45 years old.

“The building (Mishkanot Shaanaim) was dedicated early in 1861. Rabbi Joseph Nissim Burla, president of the Beth Din (Rabbinical Court), delivered a sermon praising the efforts of Montefiore and Kursheedt.”[53] Judah Touro’s name was not mentioned.

In Newport and in New Orleans proposals were made to erect a statue of Judah Touro, in his honor. The communities felt it was appropriate to recognize an American of so high a quality and caliber that others should look up to and try to emulate him. The movement failed. The religious American Jewish community very loudly objected to erecting a statue of Touro, or any Jew, as a violation of Jewish law. The Christian community let the issue go. The country was increasingly faced with a very real threat. From the North it would be called the American Civil War. From the Southern point of view it was called the War Between the States. It would tear the country apart. Over 500,000 young Americans died in the traumatic, bloody war (1861-1865). After the war, the issue of remembering Judah Touro was moot.

Fifty years after Judah’s passing the Touro Synagogue (Yeshuat Israel) in Newport, as it came by custom to be called in the 1880’s, erected a marker on the building. The memorial marker was in memory of Rev. Isaac Touro, the first minister of Yeshuat Israel and his two sons, Abraham an Judah. From the Torah an inscription was added. “The fruit of the just is a tree of life.”

June 19, 1910 a letter appeared in the New York Times. It was written by G. Wilfred Pearce. He headed a group of descendents of the veterans of the Battle of New Orleans. His proposal was to erect a statue of Judah Touro to be placed in Statuary Hall of the United States House of Representatives. He wrote:

“Never before nor since has the American flag waved in battle over as many types of nationalities and races as confronted Packenham, Burgoyne, and Cochrane at New Orleans. There were Jews, Catholics, Protestants, English, Irish, Scotch, French, Spaniards, Germans, Portuguese, Scandinavians, Greeks, Mexicans, Africans, Afro-Americans, and native stock from as far away as Maine and from almost every State of the Union. Our forces symbolized all the great races embodied for the defense of the rights of man. The Jews have done great things for us. Why should we not have a statue of a patriotic Jew in the Capitol, and if so, is not Judah Touro’s name entitled to high consideration?”

The statue of Touro was never accepted.

In the 1930’s the State House Capitol of Louisiana design called for friezes of 22 of the most influential and important citizens of Louisiana . A profile of Judah Touro was erected on the exterior walls.

Judah Touro frieze, Louisiana State House, Baton Rouge

The issue of erecting honorary statues of important American Jews, to recognize the commonality and the American Jewish experience as Americans, was no longer able to be vetoed by the Jewish observant community. A major monument project in downtown Chicago, with larger than life statues of George Washington, Robert Morris and Haym Salomon was dedicated June 16, 1941. It was the first major statuary representation of a Jew in America. The project was led by Harry Barnard, a Jewish Chicagoan. It was also the edge of World War II and Jews felt a need to visibly affirm the depths of their American heritage.

The keel of the Judah Touro, an Armadillo-class tanker, was laid by the Delta S.B. Shipbuilding Company shipyards in New Orleans, October 20, 1943. By the time the tanker ship sailed to join the American World War II fleet, she was renamed the Mink.[54]

The name Touro is proudly remembered in New Orleans. The name is associated with the preeminent hospital in the city, the Touro Infirmary which his money created in 1852. Tulane University maintains the Touro annual award.

Mishkanot Shaanaim and the famous windmill looking toward the Old City is a major tourist site in Israel today. The windmill is frequently called the Montefiore windmill. The historic community of Mishkanot Shaanaim/ Yemin Moshe is frequently, mistakenly called Montefiore. A street in the community is named Touro. A small plaque in the one of the buildings acknowledges Touro. The windmill has a small museum inside dedicated to Moses Montefiore. A single panel exhibit inside the windmill mentions Touro. Israel’s ministry of tourism has attempted to correct the history to acknowledge that it was Touro’s money that Montefiore used that created the seed that led to the establishment of the modern city of Jerusalem.

Rabbi Dr. Bernard Lander remembered Touro and his extraordinary generosity. Dr. Lander decided to create (1971) what was and is becoming one of the great learning centers of the world for law, medicine and human studies. He chose to name it Touro. The name Touro College[55] represented to Lander the moral light he wished his school to emulate.

The Israeli postal service is considering a stamp recognizing 150 years of Jewish settlement outside of the Old City. They hope to include the images of Montefiore and Touro, but only if they can get a good image of Touro.

Adulation, honor and public thankfulness to Judah Touro were almost never sought by the modest, recluse. He did his acts of charity privately and because it was the right thing to do.

Moses Maimonides, the Rambam[56], a thousand years ago, described the levels of Charitable Giving:

Maimonides: Charitable Giving

- One who gives unwillingly but nevertheless gives.

- One who gives cheerfully, but not enough.

- One who gives enough, but not until he is asked.

- One who gives before being asked

- The receiver knows the identity of the giver, but the giver does not know the identity of the receiver.

- The giver knows the identity of the receiver, but the receiver does not know the identity of the giver.

- The giver does not know the receiver, nor does the receiver know the giver.

- The highest form of tzedakah is to strengthen the hand of the poor, by extending a loan, joining in partnership, or training the poor person out of poverty, to help the poor establish themselves.

Judah Touro may have at rare times given unwillingly, perhaps not enough. At time he needed to be asked. Sometimes he knew the beneficiary of his giving and at other times he did not. But at all times his goals were the same, to strengthen the hand of the poor, by extending a loan; to join in partnership or train the poor person out of poverty; to help the poor to establish themselves.

Judah Touro did what he did because he was a Jew. To what extent he helped “repair the world” will never be known. One of his requests, after his death, was that all his records and personal papers be burned. He did not want anyone to known who or why he had helped those in need.

A good name is more desirable than great riches; to be esteemed is better than silver or gold.

Proverbs 22: 1

[1] The New Bedford Mercury, February 3, 1854

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bertram_Korn

[3] http://myweb.wvnet.edu/~jelkins/lp-2001/huhner.html

[4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Orleans

[5] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Kursheedt.html

[6] http://www.jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org/completedprgms1/neworleansla.html

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Leeser

[8] http://www.tourosynagogue.org/default.asp

[9] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/Marranos.html

[10] http://www.sephardicstudies.org/csi.html

[11] http://www.redwoodlibrary.org/notables/harrison.htm

[12] http://www.tourosynagogue.org/